China’s nuclear progress

Nuclear power in China is developing in a healthy way, regardless of critics and doubts.

In its 25-year history of nuclear electricity, China has experienced several ups and downs and several pauses – between 2003 and 2007, and between 2007 and 2010. Is the rapid development from 2010 and onwards the new norm? In the long term, maybe, and in any case the current “pause” in starting new constructions cannot be seen as a hesitation or a turning back from original plans.

The so-called 2020 target of 58GW in operation is a milestone in a much broader strategy: to follow the International Energy Agency two-degree scenario, China should have 400GW of installed capacity in 2050. Earlier, a probable new target of 150GW in 2035 would represent only 7% of the mix, at a time when the post-Fukushima Japan is planning to have above 20% of nuclear in its mix. China’s per capita electricity consumption has grown again this year, by 5%, but it is still 53% less than in Germany and only half of the 2050 forecast and target. So a two or three year slide in the current phase does not jeopardise the completion of the overall programme. Whenever the 58GW target is obtained – most probably in late 2022 – China will overtake USA as the first nuclear electricity country in the world before 2030.

In late June, after nine years of construction and many unforeseen developments, the two latest designs, the AP1000 and EPR were connected to the grid, 11 hours apart. Two weeks earlier China had signed a new contract with Rosatom including four new reactors to be built in collaboration with the Chinese nuclear industry. New projects can begin and at the end of April M. Zeng Ya Chuan, director of nuclear energy at the National Energy Administration (NEA) confirmed that “conditions are met to build in series Gen III reactors” and “the time has come to develop a new nuclear strategy for the 2035 horizon”.

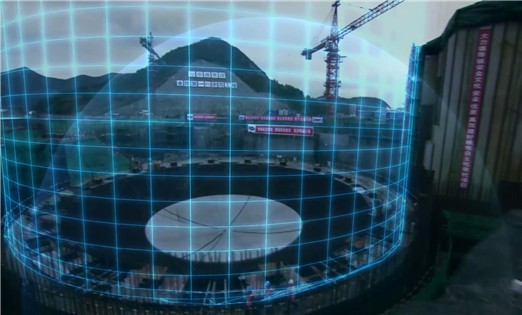

Little time has been lost, as serious preliminary works have been undertaken at: Huizhou 1&2 and Zhangzhou 1&2 for four ‘Hualong One’ projects; Sanmen 3&4, Haiyang 3&4, Lufeng 1&2 and Xudapu 1&2 for eight AP1000s and at Shidaowan for two CAP1400 projects. All these 14 reactors are waiting for imminent first concrete authorisation. Behind those, preliminary works are also under way at Changjiang, Ningde 5&6 and at six inland sites – Taohuajiang 1&2, Pengze 1&2 and Dafan 1&2 in Hubei province. Construction at inland sites was postponed after Fukushima. They are not vulnerable to tsunamis, but there was concern that after a river flood, any radioactive release would endanger the population downstream. But studies have been performed and there is new confidence that they can be launched right after 2020.

We must acknowledge that there has been at least one negative impact from the delay in new authorisations.

Engineers and technicians left the industry at a rate as high as 7.45% in Shanghai Electric and 15.7% in Dongfang Electric in 2016. But these figures must also be put into perspective, as the average employee turnover in China is 20%. Even in the very stable and mature automotive industry, it is around 6%. Around 160,000 people work in nuclear construction and the supply chain and this figure will double by 2050, but that challenge can easily be met, considering that average age of employees is under 35 and that all the technologies have been developed in domestic research institutes while the domestic industrial supply chain provides 85% of nuclear equipment.

A lot could be said about the electricity price issue. But the market is not free and open; it is controlled through benchmark prices and quotas. This makes senseless any western evaluation of profitability. Each kWh of renewable origin can be sold at 0.6CNY or 0.7CNY, while nuclear kWh is stuck at 0.43CNY. From 1 June, the solar electricity selling price benchmark has been lowered by 0.05CNY/kWh, meaning indirect subsidies have fallen by 10%. However, as solar manufacturing costs have also decreased significantly, this new move should not have any major impact on the market.

In any case, the two major operators of nuclear plants have played their cards right: in 2017, CGN’s operating income rose 29.3% and its profit rose 15.3%, despite significant growth in 2016 (up 18.2%). CNNP’s operating income also rose by 11.9%, following on from an impressive 32.4% growth in 2016.

Seeing a bright future for Chinese nuclear industry is not an illusion. Difficulties on the way cannot be considered as unsurmountable obstacles. Chinese nuclear industry leaders see role as partners with more mature industries from Russia, France, the USA and others rather than as an autonomous player; but whether they want it or not, their responsibility to ensure the success of nuclear power in the world will now only grow.